Lisbon Triennale connects architecture to culture through classification

Lisbon Triennale connects architecture to culture through classification

The fifth Lisbon Triennale promises five exhibitions, 12 special projects and plenty of architectural plans to get lost in. Rich in historical inquiry and appreciation, materials and layers, it confirms the power of architecture within culture, and suggests how classification of the past can play a powerful role in shaping the future of architecture.

itled ‘The Poetics of Reason’ and curated by Éric Lapierre, the fifth edition of the Lisbon Triennale claims that while poetics and reason may seem paradoxical, architecture is the discipline that harnesses them both. ‘Architecture is the art of giving a relevant form to a building,’ says Lapierre, architect and teacher at École d’Architecture Marne-la-Vallée Paris Est and École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne.

Rather than starting with a kernel of an idea, and throwing the Triennale open to a selection of international architects to respond, Lapierre’s exhibition ‘The Economy of Means’ is more of a manifesto. ‘Form is highly serious,’ he says. ‘Architecture should be rational, logical and understandable by everyone. Form is not private – it has the possibility of transforming the work of architects into something collective.’ Architecture holds a responsibility to resources – but not just material resources, also cultural and social resources. How can architecture communicate precisely? How can architects make walls and ceilings talk? Here is the economy, he says.

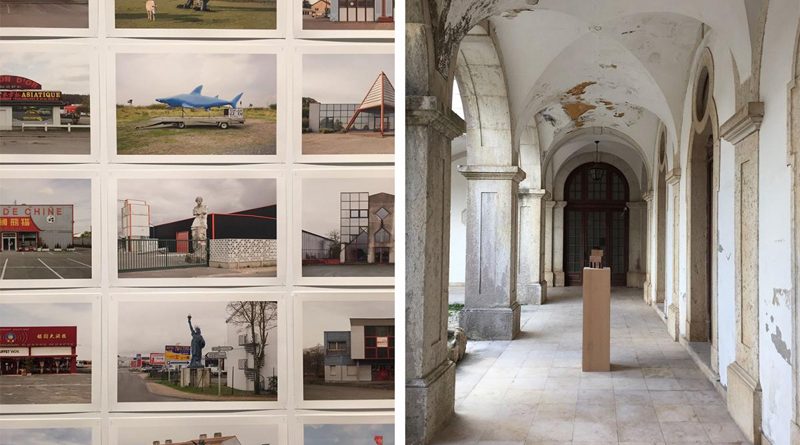

What interests Lapierre is the history of architecture as a system of knowledge, and the origins of this. The exhibition is therefore designed as a matrix ‘from which we can create an infinity of solutions’. (Lapierre follows a mantra of ‘reinvention, but not from scratch.’) So to find the DNA of a good building, our curator starts with plans and types – from photographer Eric Tabuchi’s Atlas des Regions Naturelles, to Pierre le Muet’s 17th century manual on how to build on a small plot to a survey of regional Portuguese architecture.

Classification is a means to rationalising culture. Somewhat like walking through an architecture lesson, each room addresses a new area of architecture. In one room plans of collective spaces such as the Pantheon, Hagia Sophia and Crown Hall Chicago line the floors and float on panels above. While in another, a history of small spaces unfolds featuring Kazuyo Sejima’s House in a Plum Grove, John Soane’s Dairy for Lady Craven and Charlotte Perriand’s minimum dwelling plans.

From this opening manifesto, a series of four further exhibitions spiral. Another history lesson unfolds at Garagem Sul in Sébastien Marot’s exhibition on agriculture, architecture and urbanism. The professor at École d’Architecture Paris Est presents a timeline of environmental history, a deck of 42 cards showing important images and ideas of permaculture, and four possible future scenarios. Considering industrialisation of the 20th century, he says, urbanisation seems both inevitable and impossible. His statement strikes a powerful chord, and the exhibition, aims to provide some tools for rethinking.

Curators Tristan Chadney and Laurent Esmilaire consider a tighter, yet broader, edit of case studies – from Brunelleschi to Architecten De Vylder Vinck Taillieu – in their exhibition ‘Natural beauty’ that explores the harmony of construction. Their lens is a poetic one, framing buildings with drawing and photography, and a reproduction of a delicate string model that Gaudi used for measuring the load-bearing vaults of the Sagrada Familia.

Elsewhere in the city, at Culturgest, the foundation of Caixa Geral de Depósito, ‘ornament’ is collected and classified by Giovanni Piovene and Ambra Fabi of Pivene Fabi. This time, it’s in three dimensions. Within the context of modernism, excerpts of mouldings ‘the smallest atom of ornament’, columns and patterns from architecture are curated within a sweepingly minimal scenography by Richard Venlet. As part of the show, Sam Jacob and Priya Khanchandani commissioned contemporary responses to Owen Jones’ 1856 book The Grammar of Ornament, seeking to decolonise his theories on pattern. Another treat is the restoration of Aldo Rossi’s film Ornament and crime from 1973 – a film of many films showing monuments of his personal memory.

Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli of Microcities and Socks-studio enter another dimension altogether with their exhibition ‘Inner Space’, which explores imagination. Here you’ll find something new and something unexpected for sure – from Hokusai Katsushika’s volumes of themed illustrations; Julien Rodriguez’s spatial memory maps; Valerio Oligati’s collection of pictures ‘Autobiography Iconography’; Isabel Seliger’s architectural comic strips; or Cardboard Computer’s magical realist adventure game in five acts. Here, imagination is a territory to be ‘experienced, crossed and even inhabited’.

The power of a triennial, or biennial, is its ability to reflect on the present – the reoccurring format is stable enough to be responsive to contemporary practice. Some exhibitions are better than others at applying their historical enquiries to the enquiries of the present. The most successful exhibitions align diverse lenses in unexpected ways – historical, side by side with contemporary. (If the key to the future solutions is located in the past, then we certainly haven’t found it yet, but maybe there is a code there waiting to be discovered?)

Economy of Means exhibition. Photograpy: Fabio Cunha

Economy of Means exhibition. Photograpy: Fabio Cunha

Owen Jones’ Chinese patterns in the 1856 book The Grammar of Ornament. Sam Jacobs and Priya Khanchandani commissioned contemporary responses to decolonise the patterns.OKGDVS Solo House model, featured in the ‘Economy of Means’ exhibition

Book covers featured in the ‘Agriculture and architecture: taking the country’s side

Book covers featured in the ‘Agriculture and architecture: taking the country’s side

Inner Space exhibition. Photography: Fabio Cunha

Inner Space exhibition. Photography: Fabio Cunha

Soure: https://www.wallpaper.com